September 1, 2011 by rayten

I’ve wanted to write about pricing for a long time. Finally, I have put together my first piece on a practical framework I’ve seen in action during my career. Pricing is one of the most important and hardest strategies to develop. It goes without saying that a product or company’s revenue is directly a function of their pricing model. Pricing is what drives revenue, margins and profitability.

I am not an economist and do not claim to be an expert in micro-economics, even though I am familiar with most of the basic concepts. In this blog you will not see me recommend that you set your price at the point where marginal revenue = marginal costs. In the world of internet software where marginal cost is usually negligible that concept is somewhat meaningless. Instead…

Pricing is all about capturing the value you create for a customer.

Let me explain the three core concept in more detail: creating value, capturing value and price.

Creating Value:

By definition if you have created a product or service that people are willing to pay for there is some value that you have created which is greater than your customer’s current state without it. Somehow the offering you have put together is better for your customer than doing nothing or trying to do it themselves. A few obvious examples are buying a ready-made cake at the bakery instead of baking it yourself. It may be cheaper to buy all the ingredients yourself and bake it, but it you may not have time or be willing to risk having the cake not turning out as well as the store-bought one. Thus the value created by the bakery is greater than the value of the cake you would make yourself. Net, net it is some combination of costs reduced and/or benefits created that determine the value of an offering to a customer (relative to their current state or substitute option).

We will talk a little more about this later, and without getting into too much micro-economics, the value created by an offering isn’t the same for every customer. This is basically what people refer to as the demand curve. At different prices more or less people will want to buy your product.

Capturing Value

This is one of the most important (and sometimes ‘hidden’) elements of pricing. The essence of which is, given that you create real value for customers (save money, make money, other valued benefits that are delivered) is how can you capture as much of that value that you create for customers? Is there a way to tie the price your charge to the value created for your customer? This may sound obvious and easy, but it isn’t. This is especially true if there is a big range of value created for different customers for the same product. A great example of this is Microsoft’s Excel. The value to a college student using Excel to do homework assignments etc. at school are very different compared to a management consultant building a sophisticated M&A model – yet the price is essentially the same for the two different types of customers (ignoring the small price difference between MSFT business vs. school edition of Excel).

Furthermore, a concept I like to refer to as ‘metering’ is how a product ties its price to the value it creates for customers. An easy example of this is buying a box of cereal. The metering device is the physical box that the cereal comes in that sits on the shelves at a grocery. There are usually several sizes at different price points based on the volume that you are buying. Another historically great example of metering to capture value has been the phone company. They were able to charge for long distance telephone calls where the phone company metering device was based on both the duration of the phone (i.e. number of minutes) and the distance between the callers. The phone is one of the greatest inventions but without having metering devices built in, the phone companies may not have been able to generate as much revenue. (Of course the world has change thanks to VOIP technology so this example is not as black and white as it used to be thanks to All-You-Can-Eat pricing, Vonage and Skype). I will touch a little more on this later, but building in pricing-related metering devices to capture value is a critical investment for a technology company.

Price

I am sure this is a gross over-simplification of different pricing strategies, but in my real-life experience in consumer products, enterprise and online software there are basically four ways to look at price.

They are:

- Pricing relative to costs

- Pricing relative to competition

- Pricing relative to value

- Psychological pricing

I won’t spend much time on 4. Psychological pricing which entails things like fashion and status related items or specific price points like $9.99 for a book or $0.99 for an iTunes song. These are special pricing types and I am sure there are other sources of well-research experts who can explain these less tangible and sometimes more tactical price points. Instead I will focus on the first three.

Other elements I won’t touch on here are price optimization, which to me has more to do with price elasticity (to be covered an upcoming blog) and bundling. These two concepts are ‘click down’ components that get deeper into the mechanics of your pricing strategy once you have your basic principles figure out.

1. Pricing relative to costs

This is pretty much what it sounds like – you figure out what your costs are and the determine the margin that you would like to achieve. In many industries there are standard margin expectations. Not sure how these have held up over time, but the rules of thumb I have used historically were professional services at 50%, retail food/CPG 30%, restaurants 60%. I am sure I am over-generalizing, but this type of pricing easily applies to when your customer can easily do the math on how much it would cost to find an equivalent solution to yours on their own. Since it usually isn’t worth the effort for them to build vs. buy they will choose to buy yours solution if the margin premium you are charging is reasonable. Pricing relative cost is also frequently used in commodity-like markets where there are many suppliers offering a very similar, mostly undifferentiated solution compared to yours.

2. Pricing relative to competition

The basic premise of pricing relative to competition is looking at direct competitors and substitute products for yours. For example, if something breaks in your TV or game console and you go to a repair shop to get it fixed you will compare how much they will charge you to buying a new one (all else being equal). When I worked at Kraft I was involved in launching a new dessert product and we compare equal servings of bakery desserts, versus packaged desserts versus from-scratch to get the spectrum of competitive prices to see where we would fit in.

Another example is video games. For simplicity sake let’s say Madden Football or Call of Duty costs $50, most buyers will ask themselves will I spend at least 10 -15 hours playing this game? Why? Well because they are probably comparing the entertainment value of the game versus going to watch a movie in a theater. Assuming each movie cost about $10 and lasts a couple of hours, it is pretty easy to do the math on whether or not you think the video game is worth about as much as five movies.

The less differentiated your solution is compared to alternate solutions the more you will end up with this type of pricing strategy.

3. Pricing relative to value

As discussed earlier, this is the case where you try to capture as much of the value (cost reduction and/or benefits created) that you deliver to customers. At Emmperative we tried to price our software based on the value we created. As an enterprise software company our primary value proposition was all about increasing time to market with higher quality for our customers along with some cost savings along the way. One of the challenges was selling the fuzzy revenue benefits to our pricing as customers focused on the cost savings as a way to pay for our software. In hindsight the primary challenge I think we faced is that we tried to price the software as too high a percentage of the value we were creating. Over the past 10 years I have developed a rule of thumb that you should expect to capture 10%-15% of the value you create for your customer. This way they should easily see that buying your solution will provide an order of magnitude improvement over the current state. Of course early on you could easily charge a higher percentage due to your first-to-market position, but in the longer run the 10% rule-of-thumb is pretty helpful is assessing the potential for a technology business.

One of the best models in the history of pricing relative to value is Google AdWords. When Google AdWords (and AdSense) achieved scale/network effects their auction-based pricing per click of keywords allowed them to capture almost the entire amount of value their ad/search system created for advertisers. Since most sophisticated advertisers work with some type of Cost-Per-Action the advertiser can easily do the math to figure out the value of each click and bid up to that amount and be happy paying it. As a result, Google has a near perfect system to capture the value they create all along the demand curve by having different keyword pricing for each advertiser based on what they are willing to pay. Without scale and network effects that Google has other ad network solutions can’t capture anywhere near the same value as Google does.

Picking the attributes to meter

Sometimes you have the ability to have a very dynamic and flexible price metering capability like auction-style model of Google Adwords or eBay. But many times you will need to pick specific price points. Many broad-appeal technology based solutions have a feature based two or three tiered pricing Basic/Premium or Good/Better/Best (as I saw at Intuit with their QuickBooks and TurboTax products) (note: QuickBooks is a great example where the value of QuickBooks for many customers is more than 10X what they would pay relative alternate solutions like an accountant’s hourly rate). This type of pricing basically segments the market into different user types or levels/types of functionality and prices accordingly (and may include a free version a la “freemium model”). However there are other ways to price beyond feature breadth and depth. Subscription pricing is usually time-based, enterprise solutions can be based on number of users, and others like Dropbox are based on storage capacity. Understanding the different types of customers, their segmentation based on usage and profile and what they value is the key to picking which attributes to meter.

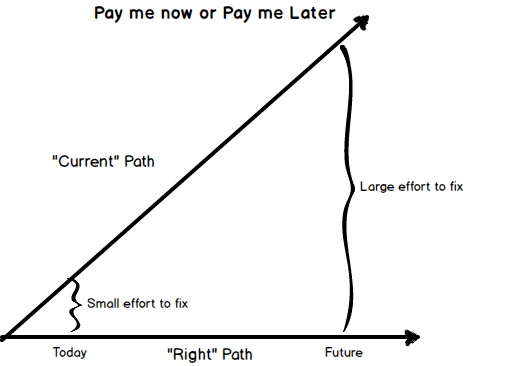

Building the metering capability into your product

It’s great that the phone company was able to allow anyone to call anyone else; a phenomenal innovation back in the day. However, the ability to measure the duration of a call and the distance between the callers was just as critical to their success as the actual phone call. I am sure a large amount of resources went into building these metering measurement and billing systems – maybe even as much effort as rolling out the telephony technology? The point being with all new ways to deliver web-based solutions these days, the effort required to build pricing-related capabilities can be a significant investment. The earlier you include this into your development plans the higher the probability of you maximizing your value-capture.

Putting it all together

Figuring out the attributes you are going use to meter the value delivered to customers and charge for early on is critical to the success of your offering/company. The earlier you build the metering (and measurement) plumbing into your offering relative to the value you create, the better your likelihood of being able to maximize your revenue potential. My experience has been that putting in the metering and measurement tools take almost as much effort to build into your product as the core functionality of the product. So if you solely focus on building the customer solution you may unknowingly be making major compromises to your revenue potential if you need to retrofit your solution or find a less optimal metering tool to charge with down the road.