As someone who has spent about half my career in startups and the other half in large organizations, I constantly compare one to the other as a way to figure out how to get the best of both worlds. There are many examples (and sterotypes) about how big companies are notoriously slow and lack innovation. Just about anyone who has worked in both types of businesses can put together a big list of pros and cons of big versus small.

The questions that I continually ask my network of former large organization leaders who now work at startups typically relate to the common challenges startups face and what could they learn from large organizations.

This post is the first in a series stemming from recurring observations and conversations I have had across many startups in which benchmarking successful large companies practices would benefit a growing startup.

To start we will discuss ‘Focus’.

There are many smart people who have already discussed the importance of focus to any organization. Just about every organization says they are focused, and even believe it. However as you start to peel the onion and ask specific questions, you can see how startups try to be clever in investing in too many opportunities at the same time. To me, in a startup there are two elements to being focused. The first is having the right amount of time, people and resources to successfully achieve a project’s goals. But the second is also not investing in additional projects that could draw on resources, cash or leadership attention that your main project could have/would have needed.

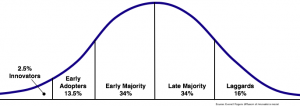

The first question I like to understand about a startup is where they are at as a company. Are they before or after product-market fit? When I worked at Emmperative we had two big customers who wanted very different enterprise marketing solutions. Coca-Cola wanted a Sales & Marketing digital asset management distribution solution while Procter & Gamble wanted a Brand Management workflow product. Let me tell you, these are very different types of products. But we wanted to keep both name-plate companies happy. So we split our engineering efforts to solve two separate jobs. Without going into all the details, our products were still so young they didn’t solve either customers needs completely.

At Adify, we hadn’t yet gotten to product-market fit with our first Build-Your-Own-Network solution, yet we were going after four completely different markets trying to see where we could get traction. Of course each of the markets had their own unique requirements, so until they began to focus on just one market segment which showed promise a lot of cash and resources were spent inefficiently.

One way to think about focus is to divide a startup’s offerings into the three buckets.

#1 Growing & profitable

#2 Fast growing, but not yet profitable (after Product-Market fit)

#3 Before Product-Market fit

If your startup is far enough along to have a product line in bucket #1, it really makes sense to keep investing in your success and allocating resources to buckets #2 and #3 (we can discuss the proportion at another time).

However most early stage startup’s primary/flagship offering is in bucket #2 or #3.

Let’s tackle the easy case first, bucket #3. If your startup has not yet reach product-market fit with its primary offering, investing in multiple offerings or customer segements will be a challenge as you dilute your focus. Even if it the same platform but targeting different markets, this will be a distraction to your team and scarce resources. Now, this doesn’t imply doing market research to seeing how close an offering could meet a different market segment’s need. Or going on a sales call to a potential customer in a different category. I am referring more to building market-segment specific capabilities into your offering that would ‘enable’ you to sell to two different customer types at the same time. This is where not being focused comes into play.

Now let’s discuss the more common situation. Where a company’s main offering(s) are in bucket #2 and yet they also are investing in new offerings in bucket #3. (And to be clear, in this case I am not talking about a bucket #3 product which is a next-generation version of a product in bucket #2. In fact I would consider that investment as part of bucket #2.) I am talking about where a company has a fast growing product that still hasn’t reached scale or profitability (bucket #2), and yet the company is investing significantly in new markets, customer segments or products (with or without the same technology platform) (bucket #3).

There is a company I know who has a phenomenal offering in market that is growing quickly, but has not yet reached scale or profitability. Thanks to that main product line’s success (with product-market fit) the company has been able to raise lots of cash. With this new cash influx, the company has invested 20%- 50% of its monthly cash burn into new products/markets that leverage the existing technology platform (bucket #3).

Here are some of the issues facing the company:

– The main product line is struggling to get to scale and profitability. The company has been able to find a market for their product and sell it, however the commercialization and operational efficiency required to get to scale has yet to occur. Management experience and organizational focus on these two areas are seen as the primary reasons.

– As the company struggles to get to profitability with their main product line, the investments in the early stage product development (bucket #3) has siphoned talent, resources and cash from the company. Their balance sheet looks weak and these new products will still require a huge investment to get to product-market fit. This has put the company in a challenging position to consider raising more cash that they really shouldn’t need if they were more focused.

– Given the lack of ability to commercialize and scale the primary offering, there is a lack of organizational confidence that even if the new offerings find product-market fit that the company will be able to scale them too.

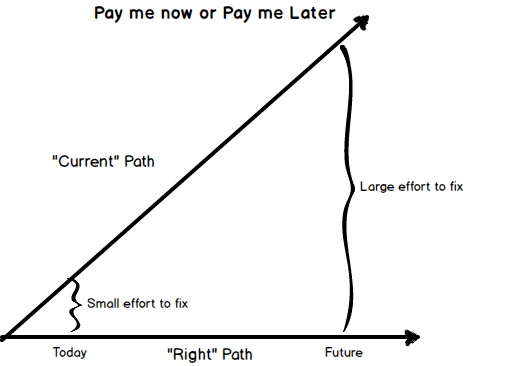

The challenges this company faces are pretty big. There are many challenges the leadership needs to address and they need to do it quickly before their cash position creates problems. Their situation is a wonderful example how the leadership did not did not make thoughtful decisions on how to keep the organization focused in a manner which struck the right balance of short term delivery of results and long term growth.

While I don’t know the right amount of resources to allocate to non-primary Bucket #3 opportunities for a early stage startup, I am sure the maximum number is less than 20% and probably more around 10%.

Larger companies with profitable product can (and should ) invest in high growth opportunities. Due to their size they can take a more portfolio management approach to their investments and balance short vs. long term growth in way that fits their ability to generate cash from their core businesses.

If you are in an early stage startup, you should ask yourself how much of the company time, people and resources are we dedicating to these Bucket # 3 (before product-market fit) opportunities? And how much is it ‘costing’ to pursue them in terms of cash, resources and management focus.