Building a great product in a weekend – is it possible?

August 16, 2011 Leave a Comment

So I’ve been thinking a lot about advice I have seen on Twitter about getting your product out there super-fast. In particular, I have pondered about the statements that encourage entrepreneurs to build a product in a weekend, launch it, get feedback, iterate and, if you can, charge money for it; all within a few days.

What I’ve been struggling with is:

Is that reasonable? Could we have done that?

Even more so, what kind of traction is reasonable to expect?

How long would it take to demonstrate enough traction to raise an institutional (VC) round from such a fast time to market?

As an early stage entrepreneur we hear a lot about finding the Product/Market fit. Which basically means figuring out if you have solved a problem with your offering that a significant number of people have. The way I describe it is ‘do we have a winner?’ i.e. is this a winning, big idea concept if we keep going with it?

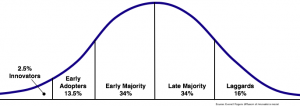

However, finding Product/Market fit and have a mass-market appeal product are different. You can probably figure out if you have Product/Market fit with Innovators as well-described in the Diffusion of Innovation Graphic:

And this is a tremendous milestone in itself, because it is very hard to get product/market fit with any sized market. But then there is the next major milestone which I call 80% product/market fit.

To me, 80% Product/Market fit means that the significant majority of users in your target market can use your offering successfully. In other words it solve the jobs they do in order to want to continue using your product again (and again). This does not mean having certain advanced features that leading edge / pro users want, but solving the problems the vast majority will need in order to adopt your product on a regular basis.

80% Product/market fit from a time perspective can occur somewhere between the latter portion of ‘Early adopters’ and the early ‘Early Marjority’. Why isn’t it a specific milestone on the graphic? Well because I am separating the product development cycle from the customer acquisition and distribution aspects of technology adoption. The graphic shows when users actually adopt the product. The product may be ready for the vast majority at times different from when users actually start using them due to the acquisition capability of the organization (sales force, channel management, social media etc.).

There is a wide spectrum of what it takes to get to Product/Market fit at the 80% level. While by no means simple, it is pretty fair to say that the timeline varies by the types of offering you are developing. Some very successful products like Instagram, Twitter, eBay, Turntable.fm surely had a much shorter time-to-market compared to complex applications like most EA titles, enterprise software, ad serving technology and popular analytical tools like Google Analytics. An interesting observation is that many of the companies that have had shorter development timelines seemed to have large amounts of user generated content and participate in markets with network effects.

There are some companies like SAP which started in 1972 and took years to build to solve enough problems (aka ‘jobs’) to become an option for large corporations in the early 90’s with R/3. Most of Microsoft’s products took several iterations to find 80%Product/Market fit. The period between MVP launch and 80% Product/Market fit could easily be measured in years (decades?).

Why I am writing this post? Well, we certainly could have been in market several months sooner if we just built what we released as our MVP. As you might recall, after building several workflows, we removed a large amount of functionality for our public release with the expectation that most will be added back in at a later time. However if we just built the MVP to start I don’t think we would have gotten our Product/Market fit to the 80% level much faster. In fact, we may have slowed it down.

Let me explain…

Because we were designing and building a product that was striving for the 80%, we made several architecture and infrastructure choices and investments that we would not have anticipated upfront had we just been building our MVP. So while we may have gotten some early traction with Innovators and very early adopters, it may have taken us longer to get to the 80% level by having to re-architect various aspects of our product at a later date (see my post The Biggest Decision). John’s perpective on this is almost always ‘better to do it now while the patient is open’, and after four plus years of working together he is usually right. Of course, it was very possible we made some investments in areas that turned out to not being needed or important so that may have worked against us. We also missed some feedback that we should have gotten sooner (Launch & Learn – quickly adapting to insights from our users), luckily that wasn’t too costly. However, on balance we feel confident we will move faster once in market to quickly get to 80%.

Since traction is so important, our speed to 80% product/market fit is what we are solving for; so that we get hundreds of thousands of users not dozens or hundreds of Innovators or Early Adopters. If we got the right initial product/market fit then our speed will be the key to our success.

If someone else has a new product that can be built in a weekend and get 80% product/market fit right away (and ideally benefit from network effects) that is awesome, and I commend them with coming up with such a great idea and opportunity. However, those opportunities are rare. I think the significant majority of meaningful companies require several months to get to 80% product/market fit and in many cases even longer.